The Other Side of the Tapestry

St. Paul, Minnesota, February, 1979

I sat in the hall waiting for the program to start. I felt alone in a room filled with hundreds of people. I had cancelled my trip to the country. Instead, I was here, in this hall full of chassidic Jews – a stranger in a strange land.

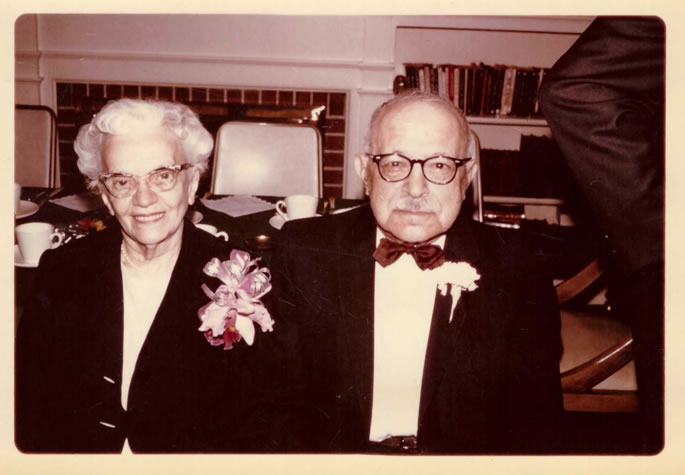

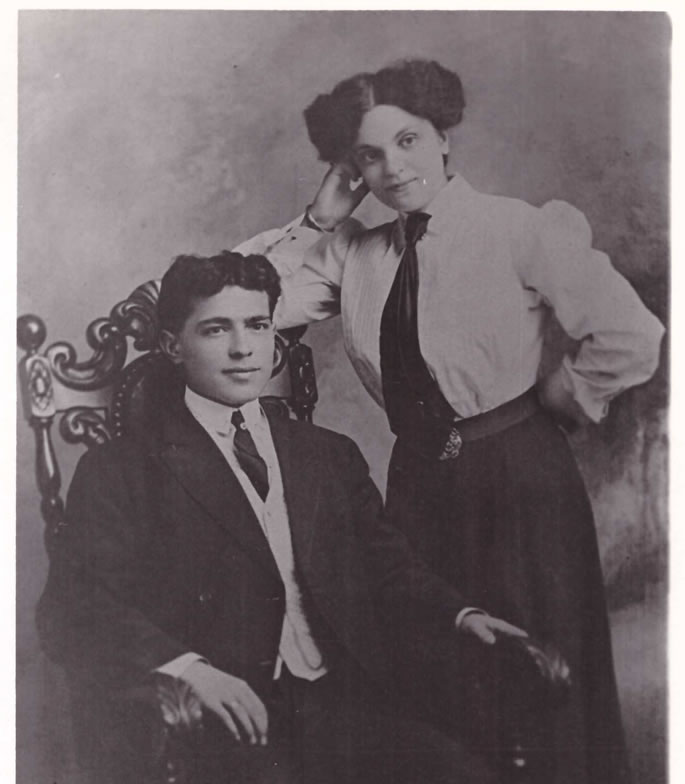

I grew up like any other middle-class American. We were Jewish, and somehow proud to be, but Judaism didn’t play a big role in my life. My mother grew up in Chicago in an observant home, and Chicago is where I lived as a very young girl. I was very close to my grandparents, especially my European grandfather, who was a warm and charismatic man, both a learned rabbi and a successful businessman. One of the most precious memories of my childhood is of Grandpa holding me on his lap while he told me stories of his own childhood – stories that seemed like fairy tales to me then.

He used to tell me about the time when his parents left Europe for America to build a better life for the family. They left him and his younger brother behind to study in the yeshiva, a traditional school of Torah-learning that didn’t exist in the America of the time. He was six years old and his little brother Max only five. The two little boys – practically babies – were left alone in the old country, in a shtetel by the name of Eisheshok. Not only did they study in the yeshiva, Grandpa told me; they slept there as well.

Imagine these two tiny boys only five and six years old, separated from their parents by the width of an ocean long before the days of telephones or airplanes, sleeping on the school benches wrapped in whatever scraps of clothing they had.

Grandpa always told me that the village they lived in was extremely poor, but since the yeshiva had no money to buy food for the kids, the community helped out by opening their homes and sharing what little they had. Often that little was almost nothing. He told me that many days all they had to eat were cucumbers. On Shabbat, they would get a piece of challah and a piece of herring in brine. Studying until late into the night, the little boys stood up over their texts up so that they wouldn’t fall asleep.

Not only did they study in the yeshiva, they slept there as well

And all of this devotion and self-sacrifice was for one purpose: to ensure that the Torah, would be passed down to the next generation in a pure and unbroken chain.

Despite the hardships he described, when my grandfather spoke of his life in the old world, somehow it seemed filled with magic and beauty to me. Although we moved to St. Paul when I was only nine years old, I still saw Grandpa several times a year until he passed away when I was nineteen. By that time I was in college, and living anything but a traditional Jewish life. But I never lost my sense of love and connection to Grandpa, or the world he so vividly described.

My grandfather’s parents worked hard, and by the time he was seventeen years old they were finally able to save enough money to bring him and his brother to America. Sadly, when he saw his mother for the first time after all of those years, he didn’t even recognize her.

Nonetheless, the foresight and self-sacrifice of his parents saved his life. Some years later, the Nazis rolled into the village of Eisheshuk. By the time they left, not one Jew was left alive. The pictures of my grandfather’s lost village now cover the tower of the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. They tell the story of a world that once was and is no more.

When I stayed overnight at my grandparent’s apartment as I loved to do, I usually slept in his office. It was lined wall-to-wall with hundreds of Hebrew texts. I was always curious to know more about what was inside those mysterious books. Grandpa told me that his collection was just a tiny fraction of the body of Torah writings. I was fascinated by the thought that any wisdom could be so vast, but nobody ever explained what all those books were about, and I often wondered what they could have to say that couldn’t be said in many fewer words.

As a young child I had an unquestioning belief in G‑d, as almost all children naturally do. But even so, and even though I was so passionately attached to my grandfather, the basics of Jewish law – things like keeping kosher, the Sabbath and other mitzvot(commandments) – seemed confusing and somewhat foreign to me.

As I said, my teenage years were typical for America at that time. I went to college, debated philosophies, dated, had fun with my friends. I never forgot that I was Jewish, but the older I became and the more I was exposed to, the more my skepticism grew. Eventually I came to define myself as an agnostic, open still to a more generic spirituality, but not particularly interested in anything Jewish. I had a hard time believing that if there was actually a G‑d, He could be very interested in me or my life. And I wasn’t very interested in learning more about the Torah; a document that included a complex set of dos and don’ts that I saw as burdensome and irrelevant to our modern times. I was far more attracted to eastern spirituality, which seemed both delightfully mystical and conveniently undemanding. I became an East Asian studies major. I also studied Japanese karate and was excited by its discipline, its meditative and mystical qualities, its mastery of body and mind. And so, life went on.

In 1973 my beloved grandfather passed away, and my grandmother followed him two years later. At that point, whatever little bit of connection to our Jewish roots my family still maintained began to erode. I knew it was over one spring when I realized I didn’t know when Passover was, and worse, that there was nobody in my family I could call and ask.

Then one day, out of the blue, my fifteen-year-old brother declared that he wanted to become observant. My reaction was… why??? Judaism is beautiful, sure, but for grandparents, not for you! It belongs in its place – in the past, in our history. Not in our real lives today.

My Journey Back Begins

But my brother’s Judaism, although he insisted on observing all of the laws, was about much more than simple dos and don’ts. As he began to study, he also began to introduce me to the wisdom that he found so compelling – the vast mystical world of Kabbalah and Chassidut. Although at first I listened just to be a supportive sister, I soon began to be intrigued by the things I heard. And the more I learned, the more intrigued I was. I found Chassidut to be profound and fascinating, and quite unlike anything I had seen or heard anywhere else. It seemed that Chassidut was able to explain some of the big questions of life – those questions I had always been told could not be answered. The more I learned, the more I felt pulled toward this wisdom, and the more I felt that what I was learning was a deeper truth than any I had ever encountered before. I wanted to respond to that truth. So with equal parts of excitement and reluctance, I decided to try two of Judaism’s most central commandments, eating kosher food and observing the Sabbath. But it was a struggle. Even though I resonated more and more with the wisdom and truth that I sensed within the words of Torah and Chassidut, I really didn’t feel at all ready for an observant life. It was simply too different, too demanding, too foreign to everything I had known before.

It was all the more foreign because, living in Minnesota, hardly any of my friends were Jewish. Nothing about my lifestyle was Jewish. The more I learned and integrated, the more I felt acutely and painfully out of place. In addition, I felt that the kind of intimate, loving, trusting relationship with G‑d that Chassidut described was too good to be true. How could I be sure that there was a G‑d at all, much less one who would notice or care about me?

So when the opportunity came up to drive to the country that Friday night with some friends, something prohibited on the Sabbath, I was very tempted to go. But at the last minute I decided to give the Sabbath one last try. I said no.

So there I sat, that Saturday night, feeling that I had very little in common with the Chassidim who filled the room, but still curious to get one final glimpse into their fascinating, mystical world.

The Rebbe’s Disciple

The white-bearded Chassidic rabbi at the dais was the guest speaker, and a disciple of the Previous Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, of righteous memory, whose passing was being commemorated this night. The Rebbe was said to be a great tzadik, a righteous and holy man on the spiritual level of Moses himself. He was said to have the power to do miracles and the Divine insight to see into a person’s soul.

His successor, who was living in Brooklyn, was the spiritual leader of the global Chabad-Lubavitch movement, and was said to have, if anything, even greater spiritual stature and powers than his predecessor.

The rabbi whom everyone had gathered to hear, Rabbi Solomon S. Hecht, lived in Chicago. He was known as an unusually talented speaker, and the small Chassidic community of St. Paul, Minnesota, had been trying to book him for a solid ten years. His talk began.

Divine Providence: The Inside Story

“I’m truly happy to be here”, began the rabbi in a deep, sonorous voice. “It’s Divine providence that I am finally here with you tonight, ten years after your community first invited me to come.

“In fact,” he continued, “It’s no accident that we’re all here together on this particular night. The Rebbe often quoted the Baal Shem Tov, first of the Chassidic masters, concerning the principle of Divine providence. He constantly emphasized that everything a person sees, he’s meant to see, and everything that he hears, he’s meant to hear. He taught that whenever something happens that makes a particularly strong impression on a person, that person needs to be aware that this experience was custom-created by G‑d specifically for him, in order to give him direction and insight in fulfilling his Divine mission.

“So,” the rabbi concluded, “The fact that I’m here tonight – together with all of you – is surely significant.”

Divine providence? I mused to myself. That’s an interesting concept. Could it be true? If so, it might be Divine providence that I didn’t make it to the country and ended up here myself.

The rabbi continued speaking. He talked only of the Rebbe, telling stories of his life – stories that illuminated his greatness, his genius, his holiness, his kindness.

Then he began a story that caught my attention. In fact, it riveted me:

A Tzadik Leaves an Impression

“At the time of the holocaust,” he said, “we had a fund. We collected money to distribute to the desperate refugees left in Europe after the war.

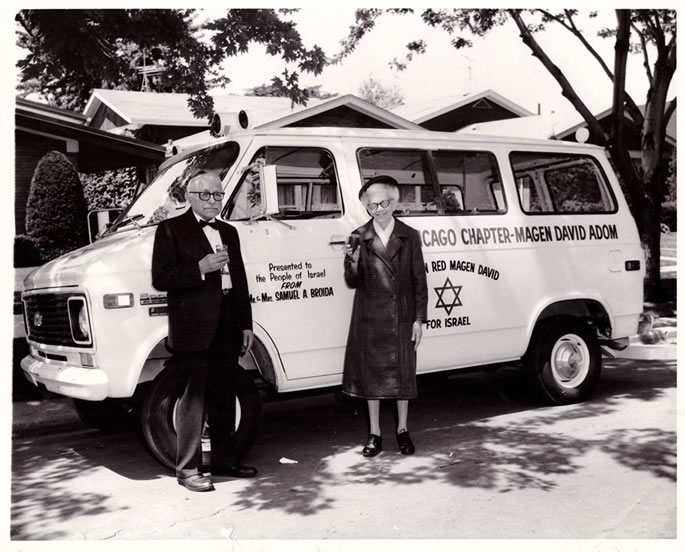

“Mr. Samuel Broida, owner of a kosher meat packaging company in Chicago, was the president of our fund.

“Altogether we managed to collect $180,000; a great deal of money at that time. Mr. Broida was delegated to take the money to Europe, to help a group of refugees who had fled from Russia to a suburb of Paris. When he returned home, he told us that something had happened to him; something he would never forget:

“‘When I was in Paris,’ said Mr. Broida, ‘I wanted to understand more about how these people lived through the difficult years of the war. So I began to speak to them. I spoke to older people, to middle-aged people, to young couples. Then, at random, I approached a little boy of about eight years old. I told him that I would be returning to America and that I would like to give him something – something special, something that he wanted very much. I asked him what that something might be. It was his answer that I will never forget.’

“So we asked Mr. Broida”, continued the rabbi, “just what this child had said that was so unforgettable.

“He answered: ‘You have to understand that these people had nothing – nothing at all. They were absolutely devastated by the war. I thought the poor little boy would ask me for shoes, clothes, food, candy, a suit, a hat… but I was wrong. He asked for none of those things. Instead, he said to me, ‘I want to have the merit to go to America and see the Lubavitcher Rebbe someday.’

“‘I myself,’ continued Mr. Broida, ‘am not a follower of the Rebbe – not at all. I’ve heard stories of the Rebbe, of his miracles, of the power of his blessings, of his holiness and greatness. But I didn’t really believe them.’

“‘But this child’s parents and grandparents were followers of the Rebbe. They came to Paris from the Russian town of Lubavitch, where the Rebbe lived until some 30 years ago. They lived close to the Rebbe until he left.’

“‘Now this Rebbe lives in America. But his influence and reputation has not diminished at all. How is this possible? How is it possible for any human being to leave such a powerful impression that he is more real to them than their hunger, their devastation or their poverty? And this was a small child! He didn’t know I would ask him this question. His answer was completely spontaneous. How it is possible that a small child, a poor child, a hungry child, wants nothing in the world but to catch a glimpse of this holy man?’

‘If a Rebbe,” concluded Mr. Broida, ‘thirty years after leaving a place, leaves this kind of impression, then it has to be because he truly is the kind of human being that the world knows nothing of. The kind of human being that I myself assumed could not exist. The kind of human being that is head and shoulders greater than the rest of us. That is what I will never forget.’”

Meeting the Rebbe

“After this,” the rabbi said, “Mr. Broida asked me if I would take him to New York to meet the Rebbe for himself. This was 1947, just a couple of years before the Rebbe’s passing. The Rebbe’s health by this time was frail. He had been imprisoned and severely tortured by the Russians who found his powerful religious leadership a great threat to the communist regime. He was able to see very few people each day and there was a long waiting list, but I managed to get Mr. Broida an appointment. And he told me afterwards that it was one of the most profound and incredible experiences of his life.”

“But then,” continued the rabbi, “Something even more amazing happened. A rebbe, like any person who receives the confidence of others, never repeats a word of what happens in a private audience between him and any other person. If a lawyer or a doctor is bound by confidentiality, how much more so a rebbe! Nevertheless, after Mr. Broida saw the Rebbe, the Rebbe called me into his office. And these were the Rebbe’s words:”

The Rebbe’s Promise

“‘Mr. Broida came in to me today,’ the Rebbe told me. ‘I asked him about his business, his community work. We talked. And when we were done talking, I asked him: And what are your children doing? He burst into tears and told me that of his six children, none were observant anymore. I promised him,’ continued the Rebbe, ‘that he would have the joy of seeing his Judaism come alive again one day in his grandchildren.’

“I have often wondered since then,” concluded the rabbi, “what happened to the Rebbe’s promise. Mr. Broida passed away years ago and I don’t know what happened to his family. But one thing I do know. The promise of a tzadik, of a rebbe, is never made in vain.”

The speech was over. I sat in my seat with tears pouring down my face.

I knew what had happened to the Rebbe’s promise.

Mr. Broida was my grandfather.

There are No Accidents

The rabbi that night began his talk with an explanation of Divine providence. That was no accident. In fact, nothing ever is.

Though he was only in his fifties, this rabbi unexpectedly passed away a short few months after this story took place. If he had not been there at that time, if I had taken the Friday night ride to the country, if he had told a different story, if he had told this one and just not mentioned my grandfather’s name, I would be living an entirely different life. And you would not be reading these words today.

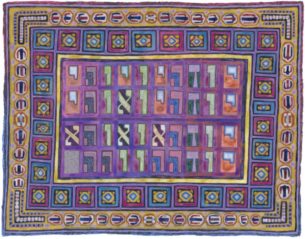

The Other Side of the Tapestry

Our lives are like the reverse side of a great tapestry. From the back, all we can see are the knots, the imperfections, some bumps, some smears of color. It all looks random and chaotic.

Only from the front side of the tapestry is it possible to see how it all fits together. From the front you can see that every stitch and every knot forms an integral part of a vast, magnificent picture.

In life, for the most part, we only see the back. We have to use our intuition, our knowledge, our wisdom, to try to fit the parts together, to guess at the picture that might be on the other side.

But on that night, I, the agnostic, was granted a rare privilege. I was given an open glimpse of the other side of the tapestry.

In that glimpse I saw many things. I saw the complex and awesome power of Divine Providence and the infinite care with which G‑d weaves together the events of every person’s unique personal life. I saw the awesome power of a true tzadik, his ability to see beyond time and beyond worlds, to reach into the reservoir of souls and empower a specific soul to fulfill its destiny. I saw the power of a Rebbe to make an impossible promise – and keep it.

And last but not least, I saw that G‑d plants messages for us all. Messages that, if we let them, can change our lives. Sometimes our messages are big and blatant, sometimes small and subtle. But they are always there if we want to see them.

When I stumbled over my destiny I wasn’t expecting it. In fact, it was the furthest thing from my mind. Yes, I was Jewish by heritage – but, as I said before, I wasn’t even sure that I believed in G‑d. But when I ran headlong into an alternate plane of reality, I saw clearly that it was vaster, deeper and far more compelling than anything I had believed possible before.

Racing Toward Destiny

That was 1979. Since then, more than my own life has changed. During the years since then, the train of history has traveled many stops en route to its ultimate destination. And its speed is accelerating day by day.

We are living today in the times spoken of by sages and prophets, in a time of transition between history and destiny, between the old order and the new. These are times of chaos, crisis and of awesome possibility. The potential is unprecedented – both for good and ill. Each of us has the choice to remain lost, helpless and afraid, or to awaken and embrace the divine power that we have been given to transform ourselves and our world.

If you choose to see the events and challenges of your life as random, you risk living as a wanderer in the dark, frustrated, disempowered, overwhelmed. But if you choose to open our eyes, to see and hear your messages, to put the pieces of the puzzle together and see the picture as it actually is, it can make all the difference – not only for you personally, but for the world at large.

The Story Continues

Much more recently, I was privileged to receive another glimpse of the other side of the tapestry – another blatant message from beyond the wall.

One evening, in September of 2006, two of my daughters attended a special inspirational program in Chicago, where they were attending school.

The school typically holds several such programs throughout the year. For most of these they rent space in local synagogues big enough to hold both students and interested community members. On this occasion, however, space was hard to come by. None of the usual venues were available. Only at the last minute were the program’s organizers able to book space in a small synagogue in a not-very-good neighborhood, somewhere they had never been before.

For whatever reason, the organizers also had difficulty finding a speaker for the occasion. However, somebody recommended somebody, who wasn’t available but recommended somebody else, who recommended somebody else…. Finally arrangements were made with a young speaker from New York whom nobody from the school had ever heard of. She was asked to speak about something that would interest and inspire the girls, but the specific topic was left up to her.

As my daughters sat in that synagogue hall, here’s what they heard. They heard a story that took place in 1979, about a young woman from Minnesota with no ostensible relationship with G‑d. A young woman whose life was changed forever because of a story that she happened to hear one cold winter’s evening in Minnesota, told by a rabbi from Chicago, a disciple of the Rebbe. It was a remarkable story of Divine providence and a message from beyond.

My daughters, that night in Chicago, heard from the mouth of a stranger the story that changed the course of their mother’s life – the story without which they would never have been born. What’s also remarkable is that they heard this story from an unknown speaker who had been flown in at the last minute from New York, recommended by who knows who, whose great-uncle “just happened” to be the rabbi who delivered the message from beyond that transformed my life so many years before.

Like her great-uncle before her, this young woman had absolutely no idea that in choosing her story she was helping to turn the wheel of destiny. How could she know that my grandfather’s great-grandchildren were sitting in that very room? And how could she know that the very synagogue in which they were sitting, the only place they were able to find for their gathering, was founded by my grandfather 50 years before, and the very place where, three times each day for decades, he came to pray.

She did not know – and yet, when the time came for her to add her thread to the cosmic tapestry, add it she did.

The Power is in Your Hands

The Blueprint teaches us to view the entire world as hanging perfectly balanced between good and bad, deserving or undeserving. That means that your one act, no matter how small, can tip the scales. It can literally make all the difference in the world.

When you live in a state of separateness, as if your life’s challenges are random and without purpose, you will inevitably be at odds with, resistant to what life brings. This state of resistance stops the flow; creates a stagnancy that makes things extremely difficult to change.

But when you connect to the fundamental truth of this world – that you, and all of the events of your life, are part of the gigantic, ever-unfolding tapestry, you and your life become one. Your mind will be clear, your heart open and serene, and the choices you make will be the made with wisdom, purpose and power. And because your awareness and your choices are in harmony with your larger purpose, doors will open before you that you could not even see before.

It’s not only that this will change your own life for the better, although it certainly will. But because each of our actions are a part of the whole, the cosmic tapestry, as we move together toward our common destiny, each bit of goodness and G‑dliness you bring into your own life will help to bring us all safely home.

By Shifra Hendrie